Another year when I did not see as many films as I would have liked, yet I still have some high points I want to share. Here are the twelve things I saw in 2015 that hit me the deepest.

Abdellatif Kechiche's The Secret and the Grain

The fact that this masterful work is little known in the States sums up the devastated state for the current American cinephile. To seek out a film like this in 2015 is to be so incredibly marginalized, so alone in your interest and passion, to survive you might have to focus on the simple positive of having been able to somehow spot Kechiche's achievement among the overwhelming wreckage. Kechiche's cinema is up to so much, all at once. Formally it is a unique mixing of Dardenne ingredients (non-actors, industrial locations, faded colors, lack of Hollywood coverage) with Cassavetes' nervy, documentary-type editing. Emotionally it is an odd pairing of Scorsese's visceral moments of discomfort coupled with Rossellini's mystic humanism. It is a much different film than the only other film I have seen so far from Kechiche, Blue is the Warmest Color, and yet another modern day classic. Kechiche is one of the greats, regardless whether our culture even knows who he is.

Hou Hsiao-hsien's The Assassin

It's always a struggle to see a film by a director you greatly admire that you are not sure you fully comprehended, particularly when you suspect you are watching some type of greatness even if you cannot seem to make sense of it all. What I do know for sure is that this is the most cinematic 2015 film I have seen, and by a longshot. It is also one of the few films I would consider a part of that rarefied group of fully sustained hypnotic works, the group that includes McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Dead Man, The Mother and the Whore, Regular Lovers, and Kings of the Road. If forced to step out and explain some of the themes or meanings that I might have caught, I would first say that it almost seemed Hou was saying about himself that he knows he is supremely talented (perhaps the most of anyone currently at work) but simply cannot allow himself like Yinniang to make the moves (or movies) that would make him more of a (commercial) success. Or like the bluebird tale that is recounted two or three times during the film, is Hou saying that he is struggling with loneliness and feelings of isolation as one of the few remaining filmmakers still truly striving to make great art? Or is he trying to tell us that he feels that if he were to allow himself to be less reserved, less ascetic, and less austere as a filmmaker and give in to what he knows would be easier commercial decisions that he would be concerned that a whole type of cinema would disappear? Again I am not fully sure what Hou is up to in his latest but in an already incredibly impressive body of work, this is probably his most purely beautiful film to date.

Hou Hsiao-hsien's The Assassin

It's always a struggle to see a film by a director you greatly admire that you are not sure you fully comprehended, particularly when you suspect you are watching some type of greatness even if you cannot seem to make sense of it all. What I do know for sure is that this is the most cinematic 2015 film I have seen, and by a longshot. It is also one of the few films I would consider a part of that rarefied group of fully sustained hypnotic works, the group that includes McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Dead Man, The Mother and the Whore, Regular Lovers, and Kings of the Road. If forced to step out and explain some of the themes or meanings that I might have caught, I would first say that it almost seemed Hou was saying about himself that he knows he is supremely talented (perhaps the most of anyone currently at work) but simply cannot allow himself like Yinniang to make the moves (or movies) that would make him more of a (commercial) success. Or like the bluebird tale that is recounted two or three times during the film, is Hou saying that he is struggling with loneliness and feelings of isolation as one of the few remaining filmmakers still truly striving to make great art? Or is he trying to tell us that he feels that if he were to allow himself to be less reserved, less ascetic, and less austere as a filmmaker and give in to what he knows would be easier commercial decisions that he would be concerned that a whole type of cinema would disappear? Again I am not fully sure what Hou is up to in his latest but in an already incredibly impressive body of work, this is probably his most purely beautiful film to date.

Maurice Pialat's Nous ne vieillirons pas ensemble

One of the last of the Pialat features I had never seen, Pialat impresses again by his strong, uncompromising approach to the medium. A French friend of mine once mentioned how revered Pialat was for his editing. I had never paid real attention to the editing until now. But here it is remarkable - forceful, edgy, propulsive and completely a piece with the rest of Pialat's form. Pialat draws Jean as a character of such unpredictable rage that the final minutes simmer and vibrate at the threat of explosive violence.

Damien Chazelle's Whiplash

One of the last of the Pialat features I had never seen, Pialat impresses again by his strong, uncompromising approach to the medium. A French friend of mine once mentioned how revered Pialat was for his editing. I had never paid real attention to the editing until now. But here it is remarkable - forceful, edgy, propulsive and completely a piece with the rest of Pialat's form. Pialat draws Jean as a character of such unpredictable rage that the final minutes simmer and vibrate at the threat of explosive violence.

Damien Chazelle's Whiplash

As much as anything I have seen in a number of years, an indy that gives me hope and belief in the future of intelligent American cinema. Chazelle impresses first by his writing. The movie is perfectly sized and veers off into directions never quite expected. Chazelle then adds two unusually well drawn lead characters with Simmons seeming to put a career's worth of power into his performance. The style is admirable, the attitude inspiring, and the balance of entertainment and art well struck.

Abbas Kiarostami's Like Someone in Love

What Kiarostami is hoping to convey I cannot say for sure. But as a long time fan of his work I took it in as a very personal statement. Here Kiarostami, one of the cinema's warmest practitioners, the lovely wise soul of Iranian cinema, is working in the middle of a Japanese metropolis. Far removed are we (and he) from the wide open expanses of his classic earlier work and we can only guess how fearful he is of our world and what it seems to be quickly becoming. Through the Olive Trees this is not. Kiarostami has entered a far darker phase and in the process might be one of the few holding up a mirror while still trying to find a way to be hopeful.

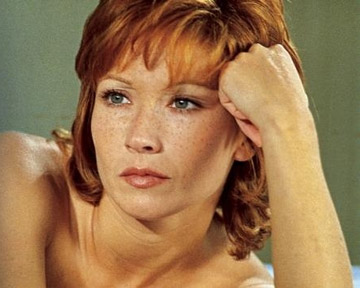

Hong Sang-soo's In Another Country

I used to think of Hong as a Korean Rohmer and there are strong similarities - a penchant for naturalism, conversation as the main action and activity, and a recurring interest in the potential disruption of relationships due to the arrival of a third person. But Hong also goes for real whimsy and seems lighter than Rohmer. In fact the more I think about it he seems like this odd blend of Rohmer and Rivette, structurally adventurous but grounded primarily in reality. Admittedly I have long had a thing for Huppert. Hong uses her well, brings out her appeal, and ends up delivering one of his smoothest, most likable films yet.

Bertrand Bonello's Saint Laurent

My first experience with the cinema of the highly acclaimed Bonello proves to be a fabulous new addition to trance cinema (Garrel's Regular Lovers, Dead Man, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, to name but a few), films that use time and the camera so effectively they lure the viewer into a near exalted hypnotic state. Bonello has a great eye and a painter's feel for texture and framing. But what most impressed me here was Bonello's completely irreverent approach to the biopic. He never feels the need to follow any of the more conventional rules for chronology or to finish any scenes or "sentences" he begins. He simply glides us through the film, and we feel all the more excited because of it.

Alex Garland's Ex Machina

Garland makes a grand entrance with his directorial debut proving a keen creator of mood, a stylist of noticeable control and restraint, a more than competent hand with his actors and a director with an eye that at its best moments conjures up memories of Welles, Tarkovsky and Kubrick. The film that I would have wanted Her to be and about as interesting of an exploration yet of where our reliance on technology might be leading us.

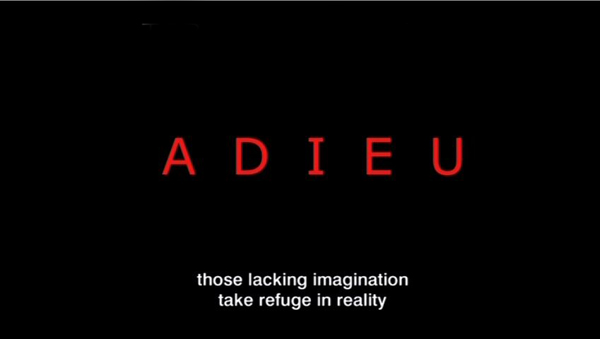

Jean-Luc Godard's Goodbye to Language

Godard's cinema is chiant; it is impossible to grasp it all. It washes over you, drowns you until you feel overwhelmed by its intelligence, superior knowledge, its grappling with something you might not even be advanced enough yet to recognize. I will be the first to admit, there is no way I can begin to analyze everything he is wanting to communicate. But it is the small ideas that jut out (Plato's "Beauty is the splendor of truth") and the arresting images of the human body, dogs, water, and cinema spooling in back of a scene that penetrate deeply. Forever, at least for me, Godard will be the one that pushes me to keep learning. Because perhaps through knowledge life can be understood. And through knowledge we might obtain beauty, truth, and make an impression on our generation, our world, and our time in life.

Oliveier Assayas' Clouds of Sils Maria

A surprisingly wise and complex film, both thematically and emotionally. Like has happened a time or two before with other filmmakers, Assayas impresses so much that I am forced to reconsider his other work and perhaps consider him as a much greater filmmaker than I once thought. The film is vital, of the present and is masterful in its exploration of age, like Dreyer's Gertrud. Binoche and Stewart are perfectly cast and turn in as great of performances as at any point in their careers.

Martin Campbell's Casino Royale

It is the first time I have seen a Craig-starring Bond film and he is quite good. First of all he might be the strongest actor of all of the Bonds and he exudes the unusual mix of charm and guile I have come to think of with Bond. The big difference is his Bond is a little more violent, a little more hands-on, more often full of visible scratches and bruises than boyish and dapper. This Bond is a bit at the end of his line and Campbell/Craig seem to have a good thing going on. The movie is non-stop action and although not always artful it is very good entertainment. In fact, after seeing this Bond, I quickly went on a tear watching the remainder of the Craig-starring Bonds as well as Goldfinger, From Russia with Love, and On Her Majesty's Secret Service.

David Simon's The Wire

Though historically I have always thought cinema deserving of a different, higher level of consideration than its domestic sibling, this work of art taught me otherwise. Nothing I saw this year impressed me more than Simon's series, in its ambition, its execution, its artistry, its acting, its depth of feeling, its camerawork, and its "filmmaking".

.jpg)